Lighting the Future

About

13 December 2023

Lighting the Future

How the first Pakistani woman with a PhD in quantum optics is bringing education to to every corner of Pakistan

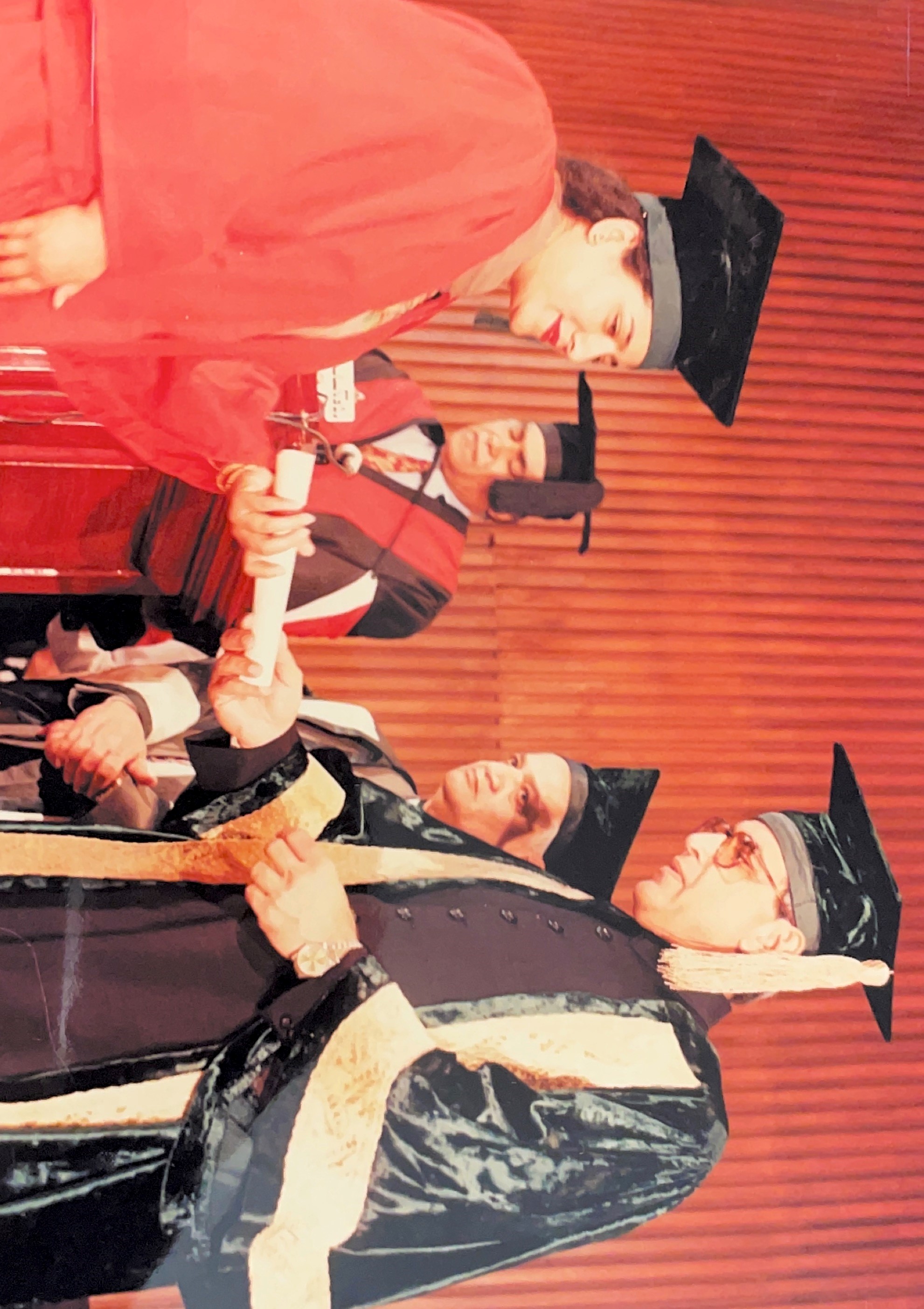

Imrana Ashraf in 2017 accepting the Spirit of Salam Award at ICTP.

When she learned that she could not be a biological mother, Imrana Ashraf decided to be a mother to disadvantaged students in her country and across the world. Growing up in a small city in Pakistan, she knows firsthand how difficult it is for many to pursue education. “Being a student in a developing country is not easy. You have limited resources. And if you are a girl, it is even harder.”

Her passion for learning started young. “I spent most of my early childhood with my maternal grandparents. I loved mathematics and science. My grandfather helped me to understand much of it. Thanks to him, when I started school, I had a good base.” She was often top of her class in her school, but after that auspicious beginning, Ashraf had to fight for her education. “Females in our family did not receive higher education. I was the first to enroll in university. There was resistance, especially from my father who worried ‘What will people say?’”

Ashraf was able to convince her family to allow her to enroll in the physics program at Quaid-i-Azam University (QAU) in Islamabad, a department launched by 1979 Nobel Laureate Mohammad Abdus Salam. She excelled, but when she wanted to pursue a graduate degree, she again faced opposition. “After undergraduate studies, there is an understanding in Pakistan that it’s time for a girl to get married. So when I wanted to enroll in my M.Phil (the equivalent of a Master of Science in Pakistan) I spoke with my maternal grandfather, who had always supported me, and he had to convince my father.”

“Being a student in a developing country is not easy. You have limited resources. And if you are a girl, it is even harder.”

During her M.Phil studies, one course set Ashraf on her career path. Sohail Zubiary, an Optica Fellow and leader in the field of quantum optics, joined the QAU faculty and offered a course on quantum electronics. Ashraf was one of a few students who enrolled—and she was immediately hooked. She knew she wanted to pursue a PhD in quantum optics. “Then I played it a bit cleverly: I knew when I completed my M.Phil there would be another discussion when I wanted to enroll in a PhD. So I converted my M.Phil into a PhD. I completed it very quickly so there wasn’t a lot of fuss at home about me becoming ‘too old to get married.’ Then I defended my thesis, and after one month I got married.” She finished her degree in just 3 years, the only woman in her cohort, ahead of her male colleagues.

Ashraf was set for a brilliant career, and she and her husband, a fellow student in her Ph.D. program, were ready to start a family. “I conceived in the first month of our marriage. But it was a problematic pregnancy and I miscarried.” While she struggled to become a mother, her flourishing career became a distraction and a source of calm. She continued to work on her postdoc with her professor, writing a book on quantum optics, and later took a job with Pakistan’s Atomic Energy Commission. In 1994, she joined her parent university QAU as an assistant professor. The workload was heavy, and she began to worry the stress was adding to her struggles. “After years of miscarriages, 2 ectopic pregnancies, rounds of IVF, and nine operations—it was really a kind of chaos—in 2000 we finally said enough. We decided we would open a school in our village for girls.”

This was a turning point for Ashraf. She was already an accomplished scientist and could have devoted her career to research and publications. But she now focused her considerable talents on those who might be left behind. “If I am a good researcher, that is for me. But if I'm an educator for others, I'm on the giving end for my community, for my students, for the girls who are left uneducated in Pakistan.”

"I thought if I couldn’t be a biological mother, I could be a good teacher for my students."

Ashraf with Gallieno Denardo, her mentor at ICTP, in 2004.

Ashraf found another avenue for giving when she attended the 2001 Winter College on Optics at the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, Italy. Participants came from all over the world to explore concepts to advance the field of optics. “There were many students from the developing world who needed help. I started teaching at night after dinner, giving informal lectures. I thought if I couldn’t be a biological mother, I could be a good teacher for my students.” She stayed for 3 months and continues to visit ICTP regularly to provide lectures in quantum optics.

Then in 2002, Ashraf received a surprising opportunity to have her own child. Her husband’s brother and his wife were expecting their fifth daughter. They knew that it had been Ashraf and her husband’s fervent desire to have a girl. “In Asian communities, no one wants a female child. But we are very strange. We wanted to have a baby girl. We never wanted a boy.” They offered Ashraf and her husband a chance to adopt, giving them the girl they had always wanted. “When she was small I told her an angel brought her down to us, which is exactly how it felt. Now that she is older she knows the truth. She is such an intelligent girl. She has come to ICTP in Italy with me many times, so she knows my ‘optics family.’”

Having her own daughter further strengthened Ashraf’s commitment to education. When the United Nations declared 2015 the International Year of Light and Light-based Technologies (IYL 2015), Ashraf stepped up to serve as one of the facilitators for UNESCO, the specialized agency of the United Nations for education, sciences and culture. In that role, she led a teacher-training workshop entitled, “Active Learning in Optics and Photonics (ALOP)” in Islamabad.

At the same time, Ashraf received a devastating diagnosis. She has four progressive autoimmune illnesses for which there is no cure: systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), dermatomyositis, Sjogren's syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. “I had two options; I could stay home and live the rest of my life being dependent on my family, or I could clear my brain, collect my energy, and live a decent life by following the doctor’s advice and taking medicines to manage my symptoms. I thought ‘I don’t have much quality time left, so I must change something for girls’ education in my country.’”

Ashraf next created Active Learning in Optics (ALO), a self-funded program under the umbrella of ICTP and QAU to bring physical sciences to underprivileged high schools and college girls in remote areas of Pakistan. “These schools, these girls, have no access to science. And optics is so easy for them to understand if we put it in their hands. It’s wonderful to see them crowding around and asking questions.” One event led to another, and since ALO’s launch, Ashraf has spearheaded more than 66 optics outreach activities all over the country.

Ashraf also formed Pak-ICTP Alumni Society (PIAS), an organization linking Pakistani students and professors who have attended ICTP. One of the chief missions of PIAS is to offer free online education, especially important since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. To date PIAS has held 30 online scientific talks, reaching thousands of Pakistani attendees. “Education is power. It has given me the freedom to speak in places where women like me have not before, to travel, and to mold my future into what I want it to be. I want others to have the same chance.”

Ashraf with Optica CEO Liz Rogan at FIO 2023, receiving the 2022 Diversity and Inclusion Advocacy Recognition.

Ashraf’s desire to create opportunities for children in Pakistan extends to transgender youth. “I am also attempting to do more for the transgender community. It is very close to my heart.” In the past few years, she has increasingly focused on diversity and inclusion, which earned her Optica’s 2022 Diversity and Inclusion Advocacy Recognition. Ashraf has received numerous other professional accolades, including the 2004 ICO/ICTP Prize, and the 2017 Spirit of Salam Award (she was the first woman in science to receive this honor). “I was a simple girl from a simple family that had placed a goal in front of me and worked to achieve it. I had gone against societal norms and expectations, which brought a certain level of judgment upon my family and me. But the results were worth it.”

Today, she continues to focus on the future through her advocacy for women’s and transgender education. She also hopes that her career has helped to inspire others to pick up the reins and give back to the world. “I want people to think about the fact that the only things that come free of cost are kindness, love and time. It doesn’t cost much to be kind, to try to understand other people and to appreciate the small things around you. Life is short, leave an impression.”

The Optica Community unites a diverse, global population of students, scientists, engineers and professionals. We invite everyone in our community to forge the connections vital to solving societal challenges through light science and technology.

Media Contact

mediarelations@optica.org

Media Contact